How to Self-Edit Your Novel: Tips for Tightening Prose from Sol Stein

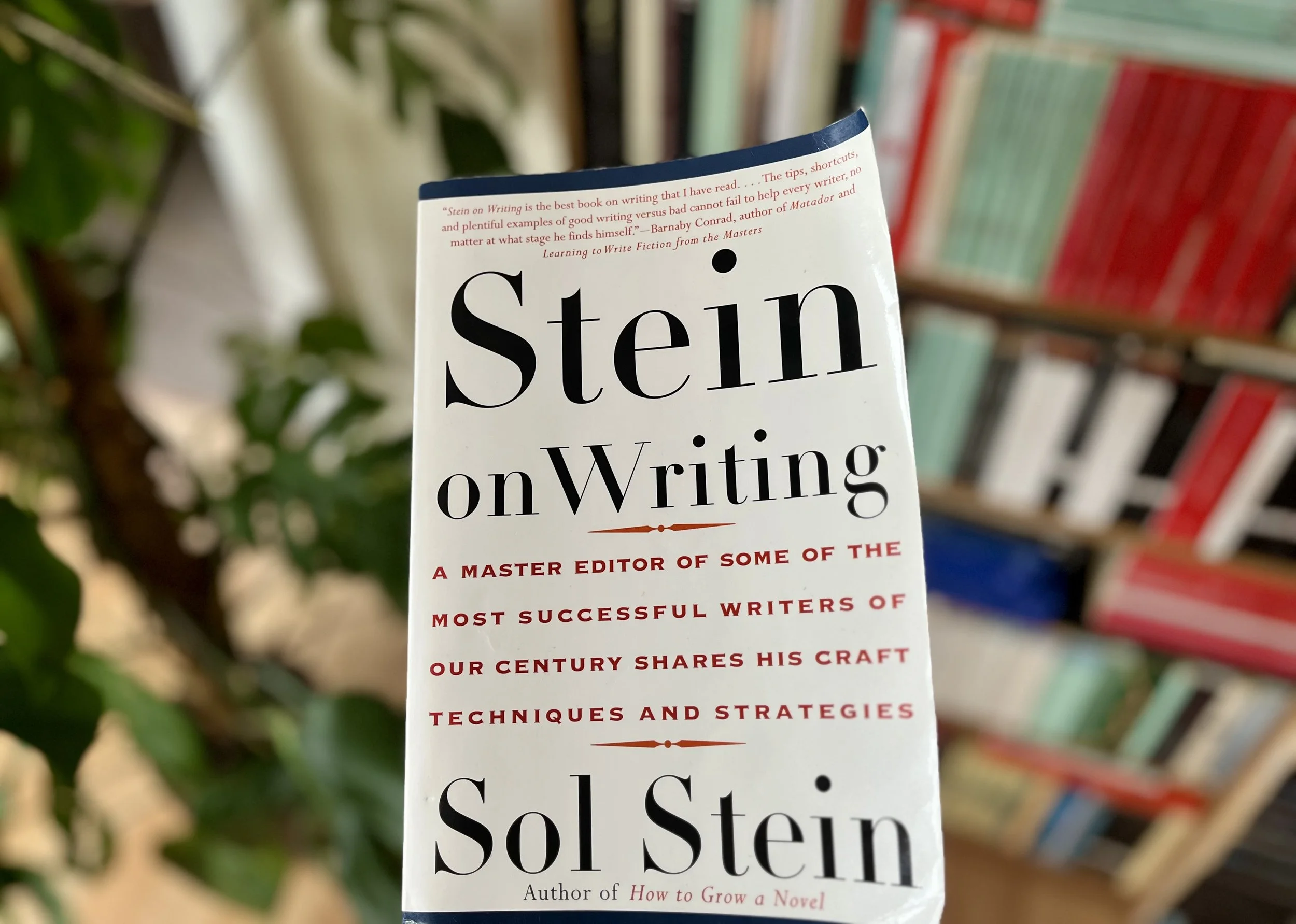

While reading Sol Stein’s Stein on Writing, I was struck by its intelligence as well as its enduring usefulness, even thirty years after it was published. The book explains fundamental craft concepts such as point of view with clarity and ease, then turns to more specialized advice on subjects including choosing the right title for your book.

However, the section I found most useful was Stein’s practical guidance on self-editing—particularly his advice on “cutting flab” to create a more powerful, concise draft.

Below is my summary of some of Stein’s top tips, along with a few of my own reflections.

Cut Adjectives and Adverbs

Stein urges writers to eliminate as many adjectives and adverbs as possible. Most of them don’t add much, and trimming them usually strengthens the text.

Look for double modifiers: If you find two adjectives or adverbs modifying the same word, keep only the stronger one.

Analyze for redundancy: Ask yourself whether the word is implied or obvious. For example, “lovely garden” doesn’t tell us much—readers generally assume gardens are lovely. But an “eerie garden” or “bizarre garden” surprises and intrigues.

Keep strong adjectives: Stein suggests retaining adjectives that (1) clarify meaning (“right” in “his right eye blinked”—without it, the character sounds one-eyed), (2) spark curiosity (“an eerie garden”), or (3) convey a precise image (“his sad mustache”—without “sad,” the phrase is just descriptive).

Keep necessary adverbs: He also recommends keeping adverbs that are necessary to convey basic meaning (“faster” in “he tried running faster”—without it, the phrase means that the character isn’t running yet) or that help the reader visualize a precise image (“she drove crazily”).

I’d add one more warning: Aderbs are particularly problematic because most end in -ly. This means that using too many of them can create a repetitive, grating sound to one’s sentences.

Cut Extra Words

As with one of my favorite tips from Matt Bird’s The Secrets of Story, Stein advises examining each sentence for words that could be removed without altering meaning. For instance,

This idea is an interesting one.

becomes

This idea is interesting.

Both sentences mean the same thing, but the second is tighter and stronger.

Stein also highlights words that often contribute little and should be cut, among which he lists however, almost, entire, successive, respective, perhaps, always, and there is.

His suggestion: Make a personal list of “flab words.” Some writers might tend toward rather or quite. For others, maybe it’s suddenly. Identifying your own habits is the first step to breaking them.

And don’t feel bad about it! I’m a suddenly overuser myself, and I remember how relieved I was when I read that Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment uses the word вдруг (suddenly) about 560 times in the Russian text. We all have our pet words, for one reason or the other, and the trick is to learn when to cut them.

Cut Extra Sentences

As with Bird, Stein extends his “flab-cutting” to full sentences. As an example, he quotes a passage from Pete Dexter’s Paris Trout:

I went there to kind of smell out what he was like. That was the last time I was in Bert Rivers’ office. From then on Bert Rivers came to my office.

Here, Stein recommends cutting the middle line:

I went there to kind of smell out what he was like. From then on Bert Rivers came to my office.

The edit removes redundancy (the middle line is implied) and quickens the pace.

Chapter endings, Stein notes, deserve special attention. This makes sense to me: I believe writers often overwrite here, feeling the pressure to produce a powerful ending. But chapter endings are one of the places where overwriting hurts most, so an especially critical revision is useful here.

Cut “One-Plus-Ones”

One of Stein’s most memorable warnings is against what he calls “one-plus-ones.” I’d first heard about Stein’s concept in James Scott Bell’s How to Write a Bestselling Novel lectures, and it was what convinced me to pick up Stein’s book.

As Stein puts it, “one plus one equals one-half.” A “one-plus-one” occurs when two phrases or sentences say essentially the same thing. Instead of doubling the impact, they halve it by competing for attention.

Examples:

“My parents, Mom and Dad”

“He was dirty. Everything about him was unclean.”

The fix? Keep the stronger version; cut the other one.

A Note on Style

Of course, no rule is universal. Sometimes writers intentionally layer words and images for effect, and it can work beautifully. Some of Stein’s suggestions are uncontroversial: cutting excess adverbs and weak modifiers such as very, for instance. But stylistic edits are subjective, and even (or especially!) the most accomplished and incisive editors will disagree over what constitutes “flab” in a work.

There’s also the matter of literary traditions. For instance, the Hebrew poetry in the Old Testament frequently employs the technique of synonymous parallelism, repeating the same idea in different words—”one-plus-ones,” as Stein would say. This clearly worked for those Old Testament authors—and contemporary writers influenced by the rhythms of Old Testament language may use similar techniques to create a stylistic effect.

Still, examining your prose with Stein’s questions in mind is a valuable exercise, and one I’d recommend to any author. If you’re nervous about cutting too much, take Matt Bird’s advice: Save a copy of your manuscript as the “Too-Short Version” and hack away fearlessly. If you regret a cut, you can always bring it back.

Final Thoughts

Cutting adjectives, adverbs, words, sentences, and “one-plus-ones” can hurt, but you’ll find a stronger, more streamlined draft emerging from the exercise. Keep in mind, however, that it’s normal to need outside help with this, especially when you’re newer to the writing and revision process. Take it as far as you can on your own, then find an outside pair of eyes to help you take it further. A professional line edit can help; so can book coaching. And the right writing partner can be a powerful aid. With each story, chapter, or novel you put through this exercise, both on your own and with outside help, you’ll grow as a stylist and find yourself cutting “flab” even before you write it.