How Evil Should Your Villain Be? Creating Believable Antagonists for Your Novel, Part I

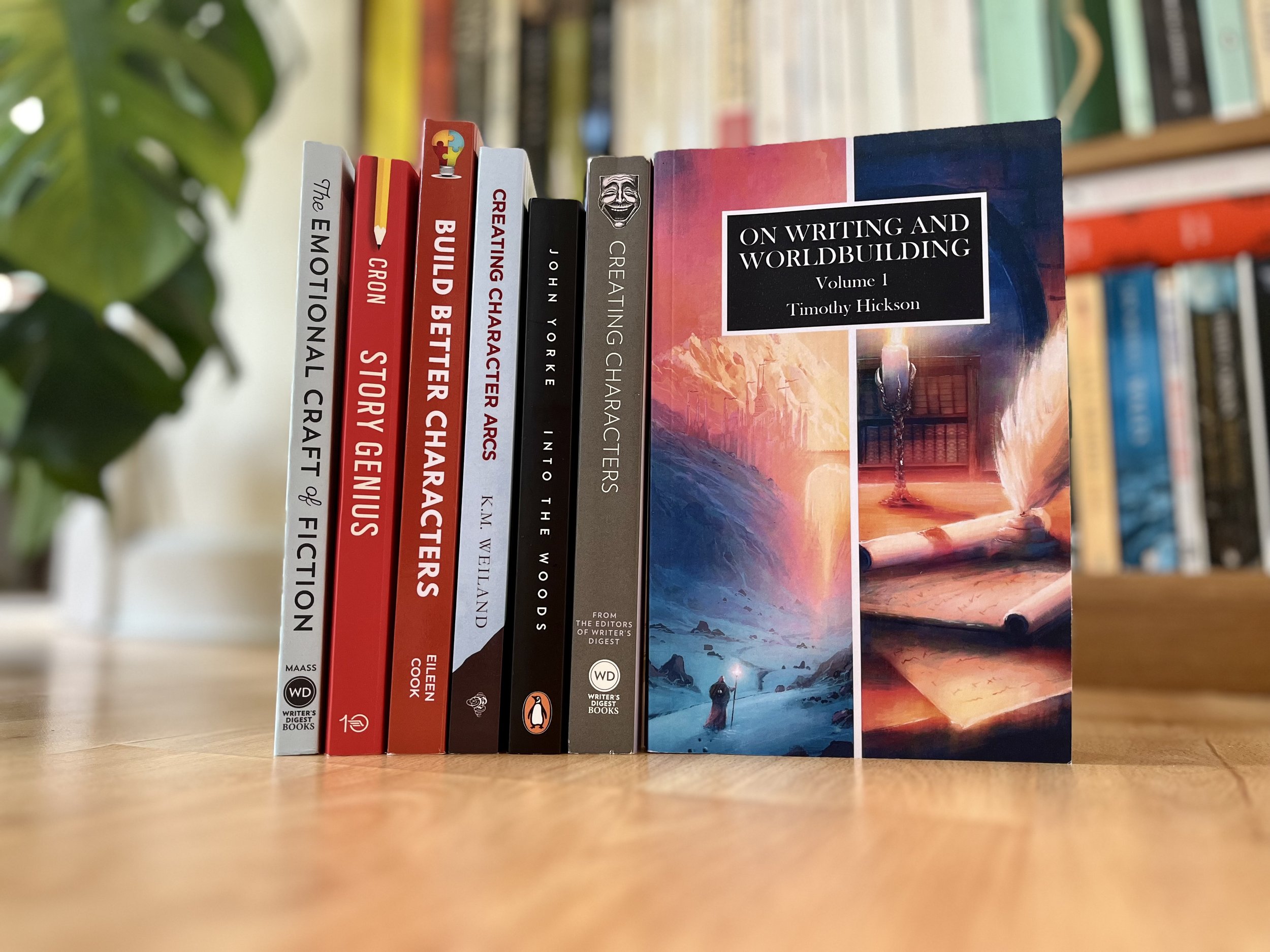

Some books that were on my mind as I wrote this post

What makes a villain interesting? Does an antagonist have to be villainous? And why do so many writers struggle with creating three-dimensional “bad guys”? These are some of my favorite questions to explore, and while I’ve been bingeing on craft books lately, they’ve occupied more and more of my thoughts.

So in my next few posts, I’ll be exploring villains and antagonists: How bad should they be? What are some tips for making them satisfying? And how can your antagonist’s motivation and backstory enhance the themes and messages of your novel?

First, let’s take a step back and look at why we write antagonists the way we do, and what it means.

Trends in Villainy, and Why They Matter

Purely evil villains have fallen out of favor over the decades, in favor of complex and even relatable or sympathetic antagonists. I link this to the reason that omniscient narration has become less fashionable in favor of writing styles that highlight and contrast individual perspectives rather than asserting there’s a single objective truth. These days, contemporary fiction, whether “highbrow” or “lowbrow,” tends to explore the complexities of “good” and “evil” and how the boundaries between these two can break down.

And it’s clear why we find this approach valuable. A century or two ago, binary worldviews made more sense (or seemed to). Today, however, googling current events brings up a wealth of contrasting perspectives. We don’t just see differing opinions from our own countries and cultures; we also see perspectives from communities with understandings of the world radically different from those we grew up with. Even within our own communities and cultures, we increasingly encounter the perspectives of marginalized groups whose experiences challenge the narratives we were taught. And we’ve learned from recent history—colonialism, missionary efforts, the Vietnam War, even pacifism and humanitarianism—that good intentions and supposedly altruistic endeavors can lead to tremendous harm.

International travel has become more accessible too. That means we’re more likely to encounter situations in which cultural norms in the community around us are ones that our own community believes are wrong or “bad”—or vice versa. Maybe you find yourself uneasy as a meat eater in a vegetarian society. Or maybe you’re gay in a culture where homosexuality is harshly punished by law and society. These types of experience demand a more nuanced understanding of good and evil. Otherwise, we risk getting trapped in the belief that entire societies are good or evil. And that way, as we’ve seen from history, lies genocide, terrorism, institutionalized oppression, and war.

So it makes sense that fiction has moved in the direction it has, from a single truth to a multiplicity of perspectives, and from good versus evil to explorations of complexity and moral grayness. (It’s not that these things are new, of course; Milton’s Satan, and Shakespeare’s complex villains, are not exactly recent! But there are times when societies are more interested in good-verus-evil/us-versus-them dichotomies, and times when questioning rigid divisions feels more necessary or relevant.)

And yet this all doesn’t make it easier to write a good villain or antagonist. In fact, it can make it harder. It demands that we put ourselves in the shoes of someone whose motives and worldviews usually oppose our own—and that can be emotionally difficult, frightening, even sometimes traumatic.

Is a “Less Evil” Villain Less Enjoyable to Read?

The hunger for complex villains and antagonists isn’t just about changing worldviews. It’s also about what’s enjoyable to read.

Some beginning writers feel that making a villain as evil as possible is necessary to create maximum tension and intensify the reader’s desire to see that character overthrown.

In fact, the opposite is often true: An antagonist who’s simply evil, who’s bad because that’s their nature, tends to be frustratingly predictable. Because we know they’re thoroughly evil, we’re never in any doubt that their next move is going to be evil. And when we’re accustomed to encountering complex, three-dimensional characters, a villain who’s bad because they’re bad tends to bore us. It can even make us feel patronized, as if the author thinks we’re not intelligent enough to respond to more complex and thought-provoking portrayals.

On top of that, an antagonist who’s simply bad can contribute to making a book feel like a lecture. That, in turn, can weaken an author’s argument rather than strengthening it. When it feels as if an author is beating readers over the head with a particular point of view, depicting its opponents as flat-out evil and wrong, readers often rebel—even if they actually agree with the author’s perspective. When an argument seems reductive, boiled down to a crudely simplified “this is good, and that’s bad,” readers feel patronized and inclined to pick holes in the author’s argument, if only to identify why it seems fishy.

On the flip side, a complex, multifaceted antagonist often creates more tension rather than less. Knowing that a character isn’t fully evil creates an element of unpredictability: Will they do the right thing this time? What about the next?

We know how frustrating a goody-goody, “Mary Sue” protagonist can be. A bad-because-they’re-bad antagonist can feel much the same: dull, predictable, boring, no matter what villainous superpowers the author gives them.

As Donald J. Maass says in The Emotional Craft of Fiction, research shows that readers want to be challenged. We want fiction that pushes us toward “thinking, guessing, questioning, and comparing what is happening [in the book] to one’s own experience”—that makes us “chew on a story,” in what he calls “the chewing effect.” And according to research, “readers are more likely to remember a story that has made them chew.” We spend more time processing it, which means it’s stored in our memory longer and we feel more deeply engaged with it.

One effective way to make your reader chew is to create villains and antagonists that make them think deeply—make them consider, then reconsider. Maybe your story’s villain has what seem to be good intentions. Maybe their actions have complex effects, with a mix of positive and negative outcomes. Maybe they do terrible things to achieve a laudable goal. Or maybe they have a backstory that’s difficult not to empathize with. A story can even call into question whether your villain is really a villain—and whether your protagonist might actually be the bad one.

These approaches all make the reader feel respected, allowed to make our own judgments—and they can create excitingly unpredictable narratives in which our beliefs are intriguingly upended.

Do All Antagonists Need to Be Morally Gray?

However, as Timothy Hickson points out in On Writing and Worldbuilding, vol. 1, this approach can be taken too far and has its own associated clichés. One piece of writing advice that Hickson takes issue with is the belief that “the most compelling antagonist is the one who believes they’re the good guy.”

Now, this piece of writing advice exists for a reason. As Hickson acknowledges, “good guy” antagonists can heighten tension and “allow the author to more easily use their motivation to further develop a theme.” The problem here is the one-size-fits-all belief that an antagonist must believe they’re the good guy.

As Hickson says, people do bad things for a lot of reasons, including fear and addiction. Some people aren’t interested in right versus wrong; they may be primarily motivated by loyalty, obligation, or necessity. These antagonists, too, can be strong.

However, whether or not these antagonists believe they’re good, they all have justifications.

Take the example of an addict. Although an addict may believe they’re bad, even evil, anyone who’s dealt with addicts has probably seen the self-justifications that accompany such behavior:

“I need to make my last binge a good one to get it out of my system.”

“I’m not strong enough to resist, so it’s not my fault.”

“Everyone says I’m bad, so what’s the point in fighting it?”

“I deserve this because the world has hurt me.”

“Everyone’s an addict in some way.”

“It’s just one drink—stop being so moralistic.”

Even when people know they’re doing the wrong thing, they make a thousand justifications. And a belief that they’re “bad” or “evil” can make the impulse to self-justify even stronger, as a defense mechanism. But that belief that they’re “bad” or “evil” is often a symptom of the fact that they aren’t: that they’re sensitive, that they have a strong sense of right and wrong, and that they’re horrified by their own behavior. Beneath the illness of addiction is a complex individual, not a black-and-white villain—even if they do terrible things and even believe they’re bad.

Of course, there are times when a relatively flat villain is effective. I’ve seen this, for instance, in certain romantic thrillers where the villain exists primarily to provide a threat that satisfies target readers because it’s predictable and simplified. Here, the narrative’s emotional complexity is meant to revolve around the protagonists, not the antagonist. And while I can’t personally see the appeal in Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, in which the villains have struck me as so cartoonish that I feel patronized by them, they’re my husband’s comfort food—and he is by no means an unsophisticated reader. So I have to chalk that up to personal taste. (Of course, Fleming’s novels are getting old, and they don’t exactly reflect current publishing trends!)

But in general, a powerful antagonist or villain needs motivations, needs justifications, needs reasons to do what they do. I think it was James Scott Bell who said that the only villain who wakes up in the morning thinking “Now, what evil am I going to do today!” is Dr. Evil from Austin Powers.

So join me next time to explore some tips for creating three-dimensional, motivated antagonists and villains!